It’s not only men who are at risk of coronary heart disease, women are too, but exercise could be one of the most important interventions, says Dr Hugh Bethell.

By far the most common form of heart disease in the western world is coronary disease. This is the condition of narrowing of the coronary arteries that supply blood to the heart muscle. Coronary artery disease leads to angina, heart attacks, heart failure and premature death. And, it is very common.

It is also called coronary heart disease (CHD). The traditional picture of the coronary patient is a middle aged, overweight male. However, women are also frequent victims of this disease. Until relatively recently, CHD was the most common cause of death in both sexes. For women, it has now been overtaken by dementia.

The coronary arteries are the vessels that take blood to your heart muscle. They arise from the root of the aorta – your body’s main artery,. They then wind around the surface of the heart in the shape of an upside-down papal crown or corona – hence their name. Their function is to supply the heart muscle with oxygen and nutrition.

What causes coronary heart disease?

CHD is caused by atheroma, or “hardening of the arteries”, a narrowing of one or more of the coronary arteries. This reduces the rate at which blood can flow through the artery. In the UK, there are around 7.6 million people living with heart and circulatory diseases, of which around 3.6 million are female, according to the British Heart Foundation.

About 175 people in the UK die of CHD every day, with CHD killing twice as many women as breast cancer. It is also a cause of much morbidity – the symptoms and limitations resulting from the disease.

Risk factors for coronary heart disease

Atheroma and coronary artery disease do not have a single cause. A number of risk factors contribute to their development. Some are irreversible, such as age (the older you are, the more susceptible you are) and gender (men develop CHD on average 10 years younger than women).

Family history also plays a role. You are at greater risk if you have a close relative with the disease. The younger that relative, the greater the risk to you.

You can’t do anything about these risk factors. However, you can tackle the reversible factors: smoking cigarettes, high blood pressure, diabetes, high blood cholesterol and obesity. Overshadowing all of these coronary heart disease risk factors though, because it contributes to most of them, is lack of exercise.

Could exercise prevent coronary heart disease?

Back in the 1950s and 1960s, studies of bus drivers and Whitehall civil servants by Jerry Morris, a Scottish doctor working at University College London, became epidemiological classics. In the former, he and his colleagues compared the rates of heart disease in London bus drivers with those of bus conductors.

While the drivers sat all day long, fuming at pesky taxi drivers and other roadusers, the conductors shinned up and down stairs getting plenty of exercise. They found that the drivers had a more than 40 per cent higher rate of CHD than the conductors.

The Whitehall civil servant study looked at leisure-time physical activity. Again, it found that the rate of fatal heart attacks in those who took vigorous exercise as recreation was about 40 per cent that of the inactive, while the rate of non-fatal heart attacks was halved.

Since then, numerous studies have confirmed the association between regular exercise, physical fitness and protection from CHD. They have shown that the greater the total of physical activity, including running, weight training and rowing, the greater the reduction in the risk of CHD. Improving a fitness level from unfit to fit nearly halves the risk compared with remaining unfit.

Some of the ways in which exercise prevents CHD are obvious, as most of the reversible risk factors are reduced. Regular exercisers are also thinner than non-exercisers, have lower blood pressure, lower blood cholesterol and are less likely to develop diabetes.

Apart from quitting smoking, if you currently do, there is no more effective way of avoiding a heart attack than by taking regular vigorous exercise.

Could exercise treat coronary heart disease?

The use of exercise for treating CHD preceded its use for treating any other non-communicable disease (a disease that is not passed on from one person to another). Back in the 18th century, Dr William Heberden recognised angina. In 1768, he described one of his patients who had been cured by sawing wood for half an hour a day.

CHD, however, was infrequently diagnosed over the next 150 years. By the time it became accepted as a serious health problem, early in the 20th century, this lesson had been forgotten. When a heart attack was diagnosed, prolonged bed rest was thought to be essential if the patient’s life was to be saved. In fact, it was believed that exertion too soon after the attack risked rupturing the damaged heart.

When the patient was eventually released from hospital, the advice was for exercise to be restricted in favour of a peaceful, sedentary life. By the 1940s and 1950s, some of the undesirable consequences of bed rest were being realised: deconditioning, boredom, depression, venous thrombosis and chest infection to mention just a few.

CHD treatment: from bedrest to exercise regimes

The idea of early mobilisation was gaining credibility. In Cleveland, Ohio, a far-seeing cardiologist called Herman Hellerstein and his colleagues developed a comprehensive rehabilitation programme with graduated exercise training as its centrepiece.

The idea was to “add life to years and perhaps years to life” for “habitually sedentary, lazy, hypokinetic, sloppy, overweight males” through a programme of enhanced physical activity. (Dr Hellerstein appears to have held his coronary patients in high regard!)

They showed that patients who had recovered from a heart attack could have their physical fitness improved, and psychological status raised, by a course of exercise. Alongside exercise, they also added improvement in nutrition, giving up smoking and continuation of gainful employment and normal social life to the rehabilitation programme.

Over the past 50 years, numerous controlled trials of cardiac rehabilitation in patients recovering from such events as heart attacks or heart surgery, have indicated a fall in the region of 25 per cent in the mortality rate in treated groups over the subsequent three years.

In patients with established coronary heart disease, exercise capacity remains a powerful predictor of prognosis. Indeed, physical fitness in CHD patients is a better predictor of longevity than any other measurement.

Which forms of exercise prevent heart disease?

For a long and healthy life and a strong, well-performing heart, exercise is the key. Exercise reduces all those risk factors that can lead to heart disease. Plus, at the same time, it ensures a high level of physical fitness and the ability to enjoy regular physical activity.

It does not matter what exercise you choose. The only important factor is that it is fun. If it’s not, you won’t keep it up! The NHS recommends 150 minutes of moderate exercise per week. This can include anything from walking and cycling to swimming and going to the gym. Take your pick! There are

any number of alternatives.

Another approach is to exercise three times per week for 30-40 minutes at a level that makes you comfortably short of breath. Any exercise is a lot better than none and the more the better. And remember to do the other NHS recommendation of muscle-strengthening exercise on two days

of the week. This could be lifting weights, push-ups or walking up a hill.

To conclude, exercise is good. It makes you healthier and makes life more fun. Perhaps, most importantly of all, it helps maintain all those activities of daily living that keep you active in later life. It also reduces the risk of ill health, frailty and dependency as the years roll by.

Calculate your risk of developing CHD

You can predict your chance of developing CHD with an online calculator. Here, you simply fill in the boxes for your vital stats. Even if you don’t have all the info required, the risk-scoring system will give you average values for missing data.

From that information, the tool will calculate your risk of developing both CHD and cardiovascular disease (CVD) over the next 10 years. Visit qrisk.org/three.

What are the most common types of heart disease?

ANGINA

Atheroma causes patchy narrowing of the coronary arteries. This is due to fatty plaques composed of cholesterol being laid down in the arterial wall and compounded by overlying thin layers of blood clot. This gradually restricts the flow of blood to the heart muscle.

A point may be reached when the artery is unable to supply the needs of the heart muscle during exercise. The muscle lacks a sufficient supply of oxygen to be able to continue to contract effectively and this produces pain during exertion, or angina pectoris.

This is a tight, strangling pain across the centre of the chest. It often radiates into the throat, jaws or left arm. It forces the sufferer to stop exercising and then settles over the next few minutes.

HEART ATTACK

The atheroma plaques are delicate creatures and may break, crack or burst. If this happens, it sets off your body’s repair mechanisms. This usually means that a clot forms. This is called a coronary thrombosis and it may be large enough to block the artery.

The result is death of the area of heart muscle supplied by that artery, called myocardial infarction. This is what we usually call a heart attack. The immediate danger is sudden death due to rhythm disturbance precipitated by the damage to the heart muscle. For those who survive to reach hospital, the outlook is good.

HEART FAILURE

The modern treatment of heart attacks is extremely effective in limiting the damage done. Even so, if there is enough myocardium (heart muscle) loss, particularly after more than one attack, this damages the heart’s ability to perform its full function. This can lead to heart failure.

The term “heart failure” sounds dire, but actually it does not mean the end of life. It simply means your heart is too weak to deliver all its potential output during daily activities.

This causes fatigue, poor circulation with cold hands and feet, breathlessness on exertion and inability to carry out the tasks of daily living. If inadequately treated, it may cause ankle-swelling and breathlessness while at rest or when lying down at night.

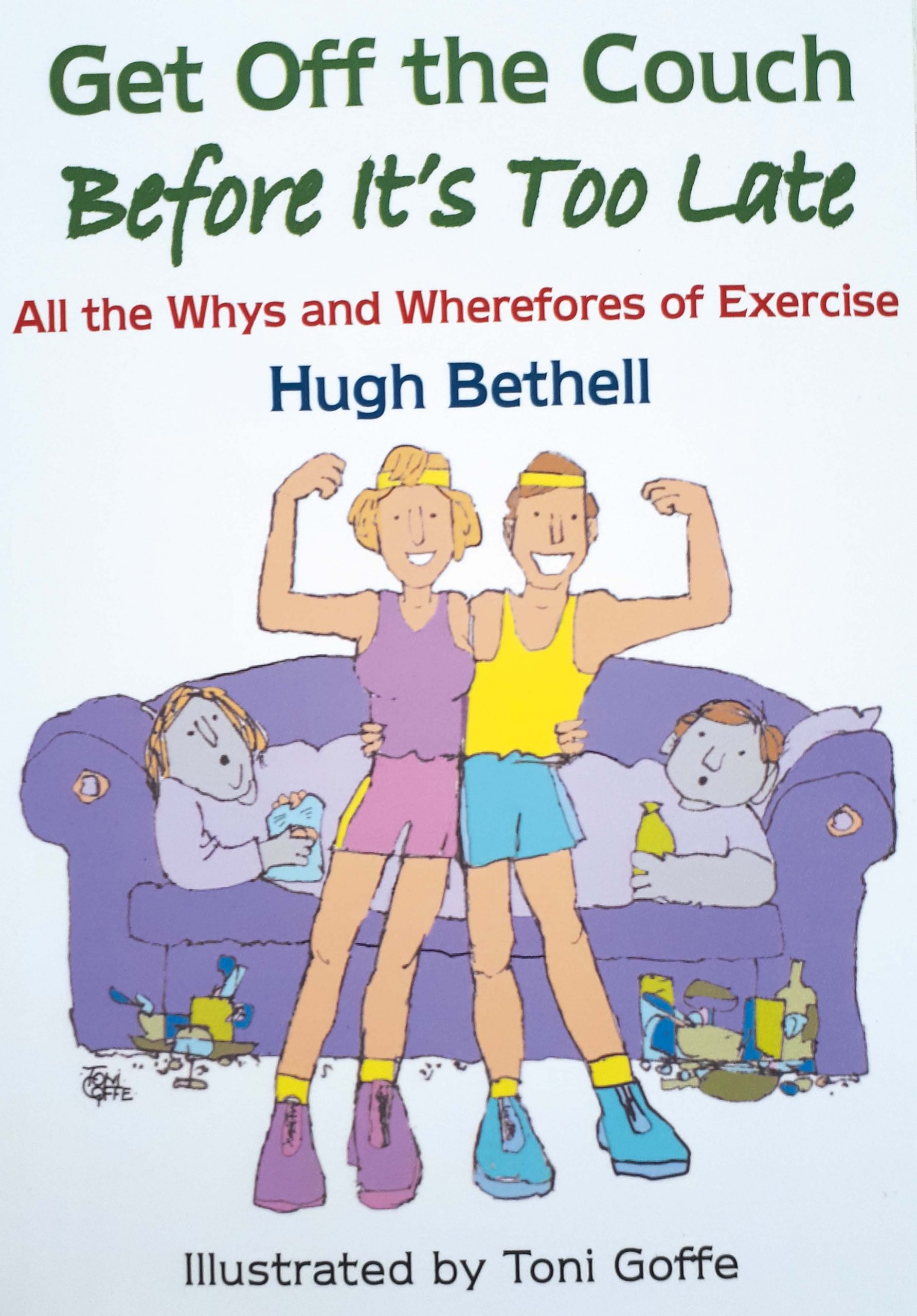

Dr Hugh Bethell has written extensively on exercise for heart disease and his latest book is Get off the couch, before it’s too late! All the Whys and Wherefores of Exercise (£14.99).

Dr Hugh Bethell has written extensively on exercise for heart disease and his latest book is Get off the couch, before it’s too late! All the Whys and Wherefores of Exercise (£14.99).

In the early 90s, he was the driver for setting up the British Association for Cardiac Rehabilitation (now the British Association for Cardiovascular Prevention and Rehabilitation) and became its first president.

His aim is to encourage regular physical activity for all for disease prevention, increasing longevity and, most of all, leading to a healthy, enjoyable old age.